Getting a Hold of Mixins in TypeScript

January 16th, 2023 — 6 min read — Gideon Idoko

Mixin is a generic term that has been in object-oriented programming for some time. The term is said to have been drawn from the noun "mix-in,” a trademarked term belonging to the owner of an ice cream shop a long time ago. At the time, mix-ins (not mixins) were extra items blended into ice cream, probably to change its taste.

Let’s come back to the technical world. The keyword “addition” can be taken from the origin started above. As mix-ins are additions to ice cream, so are Mixins additions to classes in OOP.

In this article, you'll learn about mixins in TypeScript, how they work, and their main use case.

What is a Mixin in TypeScript?

A mixin in TypeScript is a pattern that uses generics and inheritance to extend or add to the functionality of a class. In essence, mixins allow more functionality to be “mixed in" to a class.

Though Mixins are not unique to TypeScript, they play a huge role in multiple inheritance in TypeScript. This is because TypeScript supports only single inheritance. Let’s start by looking at the following classes:

class GasolineCar {

constructor() {

console.log('Gasoline car constructor');

}

}

class ElectricCar {

constructor() {

console.log('Electric car constructor');

}

}

class HybridCar {

constructor() {

super();

console.log('Hybrid car constructor');

}

}

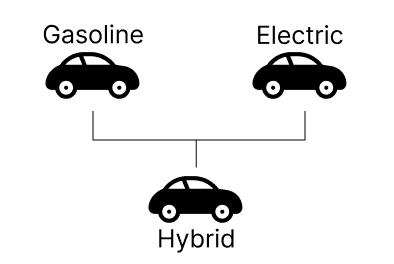

These classes represent three different types of cars: gasoline, electric, or hybrid (both).

Ideally, the first two classes should be extended to the HybridCar class since it should have all of their properties. You can attempt to extend the classes as in the code below:

class HybridCar extends GasolineCar, ElectricCar { // ❌ Classes can only extend a single class.

constructor() {

super();

console.log('Hybrid car constructor');

}

}

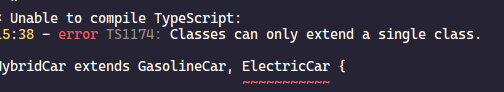

If you run this through the TypeScript compiler, you’d get the below compilation error:

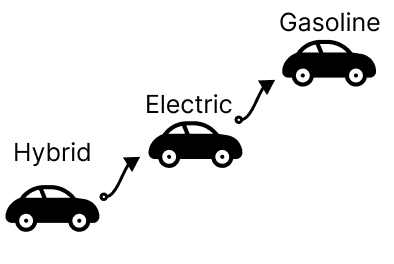

One workaround for this inability of the HybridCar class to extend multiple classes would be to create a chain of inheritance (a multilevel kind of inheritance).

Putting this in code, you’d have:

class GasolineCar {

constructor() {}

public fuel() {

console.log('Car was fueled');

}

}

class ElectricCar extends GasolineCar {

constructor() {

super();

}

public charge() {

console.log('Car was charged');

}

}

class HybridCar extends ElectricCar{

constructor() {

super();

}

}

I have added the fuel() and charge() methods to the GasolineCar and ElectricCar classes, respectively, to represent distinct behaviour.

Now, the HybridCar class has the properties and behaviours (methods) of both the ElectricCar and GasolineCar classes:

new HybridCar().charge(); // LOG: Car was charged

new HybridCar().fuel(); // LOG: Car was fueled

Here’s the catch: due to this chain of inheritance, the ElectricCar class now has the behaviour of the GasolineCar class, which you’d agree with me is a terrible idea. I mean, an electric car should'nt be fueled, right?

new ElectricCar().charge() // LOG: Car was charged

new ElectricCar().fuel(); // LOG Car was fueled

The ElectricCar and GasolineCar classes should have their own separate properties and methods. It can be concluded based on this that chain of inheritance is a bad design.

It is also worth noting that multiple inheritance can result in what is known as the "diamond problem” where, for example, HybridCar will have multiple copies of the parent (say, the Car class) of ElectricCar and GasolineCar.

Don’t forget that the goal here is to allow classes like the HybridCar class to extend the behaviours of multiple classes. Unfortunately, multiple inheritance is not provided to us here—this is where mixins shine. Mixins to the rescue!

Applying Mixins

Mixins can be applied via two (2) patterns:

- Copying prototype properties (older pattern).

- Using a factory method.

Let’s talk about both patterns outlined above.

Applying Mixins by Copying Prototype Properties

This pattern leverages object prototypes by copying all properties from the prototype of multiple classes (say the ElectricCar and Gasoline classes) to another one (say the HybridCar class). The TypeScript docs provide us with the below function that copies prototypes’ properties using the Object.getOwnPropertyNames(), Object.defineProperty(), and Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor() methods:

function applyMixins(derivedCtor: any, constructors: any[]) {

constructors.forEach((baseCtor) => {

Object.getOwnPropertyNames(baseCtor.prototype).forEach((name) => {

Object.defineProperty(

derivedCtor.prototype,

name,

Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor(baseCtor.prototype, name) ||

Object.create(null)

);

});

});

}

The applyMixins function takes the base class as its first argument and an array of classes that the base class should extend as the second argument. It will apply the properties and behaviour of all the classes in the array as mixins into the base class at runtime. Because the mixins are applied at runtime, a static type error will be thrown. Hence, a separate interface (which exists at compile time) has to be created to declaratively merge the type of all classes in the array argument.

Let’s utilize the applyMixins to apply the mixins (from GasolineCar and ElectricCar) on HybridCar:

class HybridCar {

constructor() {}

}

applyMixins(HybridCar, [GasolineCar, ElectricCar]);

// an interface with the same name as a class merges the type

// of the interface to that of the class (declarative merging)

interface HybridCar extends GasolineCar, ElectricCar {}

new HybridCar().fuel(); // LOG: Car was fueled

new HybridCar().charge(); // LOG: Car was charged

Now, HybridCar will have all properties and methods of GasolineCar and ElectricCar.

Applying Mixins via a Factory Method

This pattern makes use of a factory method which returns a class expression that extends the base class. This factory method relies on generics to add proper static typing for the expected base class.

Let’s look at the below code:

type Constructor<T = object> = new (...args: any[]) => T;

function MakeGasoline<TBase extends Constructor>(Base: TBase) {

return class extends Base implements GasolineCar {

fuel() {

console.log('Car was fueled');

}

};

}

function MakeElectric<TBase extends Constructor>(Base: TBase) {

return class extends Base implements ElectricCar {

charge() {

console.log('Car was charged');

}

};

}

const NewHybridCar = MakeElectric(MakeGasoline(HybridCar));

new NewHybridCar().fuel(); // LOG: Car was fueled

new NewHybridCar().charge(); // LOG: Car was charged

Here, the generic type Constructor defines the expected type of the base class. The MakeGasoline and MakeElectric factory methods apply mixins for adding gasoline and electric car methods respectively to the base class (HybridCar). The class returned by the factory methods above implement the GasolineCar and ElectricCar classes separately to ensure appropriate behaviours are “mixed in”.

Now, HybridCar will have the properties and methods of GasolineCar and ElectricCar.

Wrap Up

Mixins come in handy especially when your software design demands that you model your code in such a way that certain classes inherit multiple behaviours from others. In this article, you learned about mixins, a pattern that enables multiple inheritance. You also learned about the chained inheritance and why it's a bad design. You went on to look at two patterns for implementing mixins in TypeScript.

Needless to say, mixins can be implemented in more advanced ways. I’ve added links to articles that touch them if your care to read further.

I hope this article has helped you to better understand mixins and how to use them. Kindly share if you found it helpful.

Thanks for reading and happy grinding😁!